[GUEST ACCESS MODE: Data is scrambled or limited to provide examples. Make requests using your API key to unlock full data. Check https://lunarcrush.ai/auth for authentication information.]  Niels Groeneveld [@nigroeneveld](/creator/twitter/nigroeneveld) on x 12.8K followers Created: 2025-07-20 18:57:55 UTC Mountain of Defiance: The Enduring History of the Druze in Sweida High on the basaltic plateaus of southern Syria lies the province of Sweida, once known as Jabal al-Druze—Mountain of the Druze—a name that holds far more than geographic meaning. It is a title that reflects centuries of resilience, identity, and refusal to bend to the designs of empires, regimes, or religious homogenization. The history of the Druze in this region is not just a local chronicle but a foundational narrative in the broader history of Syria, rooted in esoteric theology, strategic migration, armed resistance, and an unyielding defense of communal autonomy. The roots of Druze presence in Sweida stretch back nearly a millennium. Though the Druze faith itself was born in the crucible of 11th-century Fatimid Egypt, its adherents soon found themselves hunted following the disappearance of Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, whose deification had been a central tenet of early Druze belief. This led to a diaspora in which survival depended on retreating to inaccessible highlands. While Mount Lebanon became the first major stronghold, the fertile volcanic slopes and remote ridges of Jabal al-Arab would, over the centuries, draw Druze migrants from both political necessity and spiritual calculation. By the late 13th century, traces of Druze settlement appeared in what would become Sweida. But it was not until the 18th and 19th centuries—particularly during the waning decades of Ottoman rule—that the region’s demographic and cultural identity as a Druze enclave solidified. The violent upheavals of 1860 in Mount Lebanon and Damascus, where Druze were embroiled in devastating sectarian clashes with Christians, triggered a dramatic southward migration. Entire families fled into the protection of the Syrian highlands, bringing with them not only their religious customs but also their traditions of leadership, tribal structures, and martial readiness. Among them were the al-Atrash, a family destined to leave a permanent imprint on the politics and mythology of the region. Under Ottoman administration, Sweida remained semi-autonomous. Its rugged terrain and cohesive communal leadership rendered it difficult to govern. Druze sheikhs, increasingly unified under figures such as Ismail al-Atrash, exercised de facto sovereignty. Their power was often based less on formal recognition and more on their ability to deliver security and resolve conflicts internally—while resisting both conscription and taxation from Istanbul. The result was a region that functioned outside imperial reach, where Ottoman authority was tolerated but never truly accepted. That tradition of localized self-rule and defiance found its most famous expression in the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925. Sparked in Sweida by mounting French colonial arrogance and the provocative arrest of local sheikhs, the revolt quickly escalated under the command of Sultan Pasha al-Atrash. More than just a tribal insurrection, this was a nationalist rebellion that transcended sect, ethnicity, and class. From the mountains of Sweida, a call went out to all Syrians, and for a brief moment, the fragmented land found a unified purpose. Although the revolt was ultimately crushed by French artillery and airpower, it earned the Druze eternal respect as one of the few communities to have taken a stand, not just for themselves, but for a vision of an independent Syria. With the end of the French Mandate and the emergence of modern Syria, the Druze of Sweida entered a complex and often uneasy relationship with the central government. The state recognized their role in the struggle for independence but viewed their persistent autonomy with suspicion. Leaders like Adib Shishakli sought to subdue the region through military campaigns, culminating in the 1954 shelling of Sweida. Yet the Druze held their ground, weathering coups, ideological purges, and the Ba’athist reengineering of Syrian society that followed. Under Hafez al-Assad’s rule, the regime pursued a cautious strategy toward Sweida. Druze officers were elevated to high military ranks, and the province was largely left to manage its own religious and internal affairs—so long as its political ambitions remained muted. The intricate system of Druze religious hierarchy, closed to outsiders and deeply secretive even to uninitiated members of the faith, remained untouched by Ba’athist secularism. While loyalty to the state was often proclaimed, the unwritten code of the mountain—al-murū’a, or dignified self-reliance—was never surrendered. When Syria began its descent into civil war in 2011, Sweida once again became an exception. It did not join the early uprising, nor did it fall under the control of Islamist factions. Instead, the region charted its own path, navigating the chaos through localized defense forces, tribal councils, and religious leadership. Armed neutrality became the doctrine. The Rijal al-Karama, or Men of Dignity, emerged not as a militia in the conventional sense but as a community-based force rejecting both forced conscription by the Assad regime and extremist encroachment from outside. This position grew increasingly difficult to maintain. As jihadist groups swept across much of southern Syria, Sweida became a last redoubt of local order. When ISIS infiltrated the region in 2018, murdering and kidnapping scores of civilians in a brutal assault, the people of Sweida responded not with pleas for external help but with an armed counteroffensive launched by local fighters. In the wake of the attack, distrust of Damascus deepened; many accused the regime of deliberately weakening the area’s defenses or even of complicity in the attack. By 2023, that simmering anger boiled over. Amid economic collapse and state abandonment, Sweida erupted in protest—this time not in defense of ancient autonomy, but in demand for dignity and change. For the first time since the uprising of 2011, a major Syrian city took to the streets openly calling for the downfall of the regime. Yet unlike other regions, Sweida’s movement was disciplined, peaceful, and rooted in a deep tradition of moral authority. Druze sheikhs, tribal elders, students, and women all joined together, invoking both the spirit of Sultan al-Atrash and the spiritual code of resistance embedded in their theology. Today, Sweida stands apart not because it is untouched by crisis, but because it is defined by community resilience in the face of it. While much of Syria has descended into factionalism, proxy wars, or acquiescence, the Druze of the mountain continue to believe in a different kind of future. They are not utopians; their sense of history is too long for that. But they are not defeated either. In the heart of a broken country, Sweida endures—unbending, watchful, and still whispering the sacred truths of a people who have survived by keeping faith with themselves.  XXX engagements  **Related Topics** [syria](/topic/syria) [druze](/topic/druze) [Post Link](https://x.com/nigroeneveld/status/1947008085840548306)

[GUEST ACCESS MODE: Data is scrambled or limited to provide examples. Make requests using your API key to unlock full data. Check https://lunarcrush.ai/auth for authentication information.]

Niels Groeneveld @nigroeneveld on x 12.8K followers

Created: 2025-07-20 18:57:55 UTC

Niels Groeneveld @nigroeneveld on x 12.8K followers

Created: 2025-07-20 18:57:55 UTC

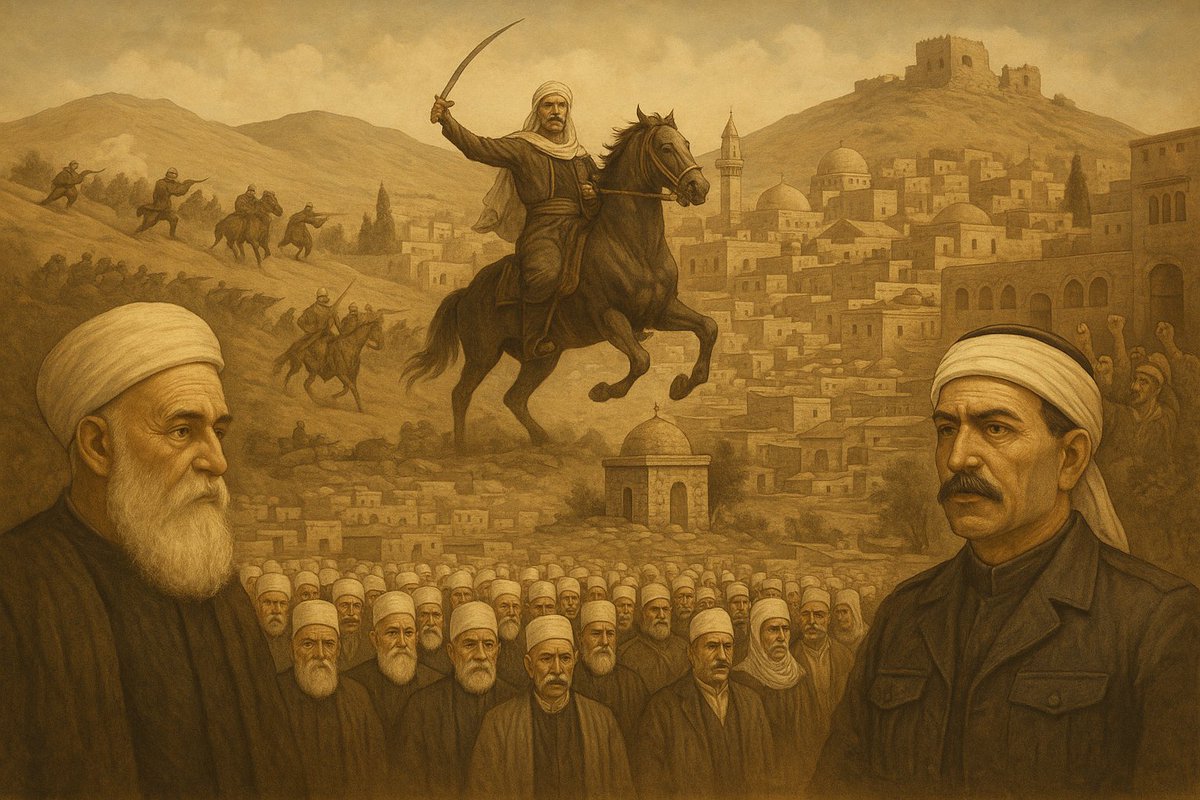

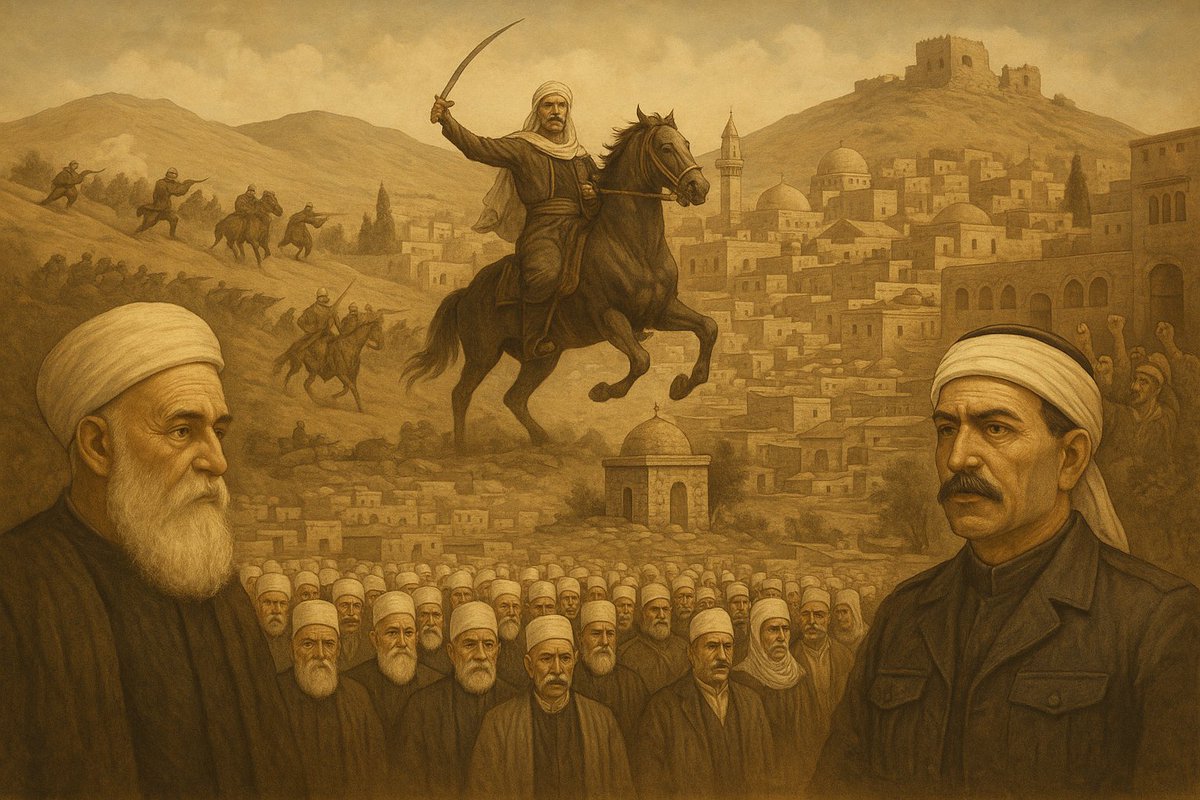

Mountain of Defiance: The Enduring History of the Druze in Sweida

High on the basaltic plateaus of southern Syria lies the province of Sweida, once known as Jabal al-Druze—Mountain of the Druze—a name that holds far more than geographic meaning. It is a title that reflects centuries of resilience, identity, and refusal to bend to the designs of empires, regimes, or religious homogenization. The history of the Druze in this region is not just a local chronicle but a foundational narrative in the broader history of Syria, rooted in esoteric theology, strategic migration, armed resistance, and an unyielding defense of communal autonomy.

The roots of Druze presence in Sweida stretch back nearly a millennium. Though the Druze faith itself was born in the crucible of 11th-century Fatimid Egypt, its adherents soon found themselves hunted following the disappearance of Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, whose deification had been a central tenet of early Druze belief. This led to a diaspora in which survival depended on retreating to inaccessible highlands. While Mount Lebanon became the first major stronghold, the fertile volcanic slopes and remote ridges of Jabal al-Arab would, over the centuries, draw Druze migrants from both political necessity and spiritual calculation.

By the late 13th century, traces of Druze settlement appeared in what would become Sweida. But it was not until the 18th and 19th centuries—particularly during the waning decades of Ottoman rule—that the region’s demographic and cultural identity as a Druze enclave solidified. The violent upheavals of 1860 in Mount Lebanon and Damascus, where Druze were embroiled in devastating sectarian clashes with Christians, triggered a dramatic southward migration. Entire families fled into the protection of the Syrian highlands, bringing with them not only their religious customs but also their traditions of leadership, tribal structures, and martial readiness. Among them were the al-Atrash, a family destined to leave a permanent imprint on the politics and mythology of the region.

Under Ottoman administration, Sweida remained semi-autonomous. Its rugged terrain and cohesive communal leadership rendered it difficult to govern. Druze sheikhs, increasingly unified under figures such as Ismail al-Atrash, exercised de facto sovereignty. Their power was often based less on formal recognition and more on their ability to deliver security and resolve conflicts internally—while resisting both conscription and taxation from Istanbul. The result was a region that functioned outside imperial reach, where Ottoman authority was tolerated but never truly accepted.

That tradition of localized self-rule and defiance found its most famous expression in the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925. Sparked in Sweida by mounting French colonial arrogance and the provocative arrest of local sheikhs, the revolt quickly escalated under the command of Sultan Pasha al-Atrash. More than just a tribal insurrection, this was a nationalist rebellion that transcended sect, ethnicity, and class. From the mountains of Sweida, a call went out to all Syrians, and for a brief moment, the fragmented land found a unified purpose. Although the revolt was ultimately crushed by French artillery and airpower, it earned the Druze eternal respect as one of the few communities to have taken a stand, not just for themselves, but for a vision of an independent Syria.

With the end of the French Mandate and the emergence of modern Syria, the Druze of Sweida entered a complex and often uneasy relationship with the central government. The state recognized their role in the struggle for independence but viewed their persistent autonomy with suspicion. Leaders like Adib Shishakli sought to subdue the region through military campaigns, culminating in the 1954 shelling of Sweida. Yet the Druze held their ground, weathering coups, ideological purges, and the Ba’athist reengineering of Syrian society that followed.

Under Hafez al-Assad’s rule, the regime pursued a cautious strategy toward Sweida. Druze officers were elevated to high military ranks, and the province was largely left to manage its own religious and internal affairs—so long as its political ambitions remained muted. The intricate system of Druze religious hierarchy, closed to outsiders and deeply secretive even to uninitiated members of the faith, remained untouched by Ba’athist secularism. While loyalty to the state was often proclaimed, the unwritten code of the mountain—al-murū’a, or dignified self-reliance—was never surrendered.

When Syria began its descent into civil war in 2011, Sweida once again became an exception. It did not join the early uprising, nor did it fall under the control of Islamist factions. Instead, the region charted its own path, navigating the chaos through localized defense forces, tribal councils, and religious leadership. Armed neutrality became the doctrine. The Rijal al-Karama, or Men of Dignity, emerged not as a militia in the conventional sense but as a community-based force rejecting both forced conscription by the Assad regime and extremist encroachment from outside.

This position grew increasingly difficult to maintain. As jihadist groups swept across much of southern Syria, Sweida became a last redoubt of local order. When ISIS infiltrated the region in 2018, murdering and kidnapping scores of civilians in a brutal assault, the people of Sweida responded not with pleas for external help but with an armed counteroffensive launched by local fighters. In the wake of the attack, distrust of Damascus deepened; many accused the regime of deliberately weakening the area’s defenses or even of complicity in the attack.

By 2023, that simmering anger boiled over. Amid economic collapse and state abandonment, Sweida erupted in protest—this time not in defense of ancient autonomy, but in demand for dignity and change. For the first time since the uprising of 2011, a major Syrian city took to the streets openly calling for the downfall of the regime. Yet unlike other regions, Sweida’s movement was disciplined, peaceful, and rooted in a deep tradition of moral authority. Druze sheikhs, tribal elders, students, and women all joined together, invoking both the spirit of Sultan al-Atrash and the spiritual code of resistance embedded in their theology.

Today, Sweida stands apart not because it is untouched by crisis, but because it is defined by community resilience in the face of it. While much of Syria has descended into factionalism, proxy wars, or acquiescence, the Druze of the mountain continue to believe in a different kind of future. They are not utopians; their sense of history is too long for that. But they are not defeated either. In the heart of a broken country, Sweida endures—unbending, watchful, and still whispering the sacred truths of a people who have survived by keeping faith with themselves.

XXX engagements