[GUEST ACCESS MODE: Data is scrambled or limited to provide examples. Make requests using your API key to unlock full data. Check https://lunarcrush.ai/auth for authentication information.]  ArchaeoHistories [@histories_arch](/creator/twitter/histories_arch) on x 233K followers Created: 2025-07-20 13:08:29 UTC The Runic Confession of Sigurd Jarlsson – A Cry from Norway’s Civil Wars .... In the doorway of Vinje Stave Church in Hordaland, a rare runic inscription tells a dramatic story from one of the bloodiest chapters in Norwegian history: "Sigurd Jarlsson carved these runes Saturday after St. Botulph’s Day when he fled here and refused to enter into a plea deal with Sverre, his father and his brothers' bane." The inscription likely dates to the late 1100s or early 1200s, during Norway’s brutal civil war era—a time when rival factions battled over the throne for generations. The man Sigurd fled from was King Sverre Sigurdsson (reigned 1177–1202), a former priest who rose to power as leader of the Birkebeiner rebel faction. Sverre claimed to be the illegitimate son of King Sigurd Munn and used this claim to challenge the reigning powers. Ruthless and charismatic, Sverre crushed his rivals, many of whom were members of the old aristocracy. Among them, apparently, was Sigurd’s family. Calling Sverre “his father and his brothers’ bane” was a direct accusation. Sigurd’s words suggest that Sverre was responsible for killing his relatives—possibly during one of the many violent clashes between the Birkebeiners and their enemies, such as the Bagler faction. Sigurd’s refusal to “enter into a plea deal” shows that he was offered a chance to submit, perhaps even survive—but he chose exile and carved his defiance into the wood of a holy place. The reference to “Saturday after St. Botulph’s Day” gives us a rare and precise date. The tone is not poetic—it’s political. This is not myth or legend, but a personal act of rebellion captured in a handful of runes. What happened to Sigurd Jarlsson afterward is unknown. But his carved message survives—one of very few medieval runic inscriptions with such clear historical and emotional force. It stands as a defiant whisper from a man trapped in the storm of civil war, unwilling to bow to the man he blamed for destroying his family. #archaeohistories  XXXXX engagements  [Post Link](https://x.com/histories_arch/status/1946920147110781119)

[GUEST ACCESS MODE: Data is scrambled or limited to provide examples. Make requests using your API key to unlock full data. Check https://lunarcrush.ai/auth for authentication information.]

ArchaeoHistories @histories_arch on x 233K followers

Created: 2025-07-20 13:08:29 UTC

ArchaeoHistories @histories_arch on x 233K followers

Created: 2025-07-20 13:08:29 UTC

The Runic Confession of Sigurd Jarlsson – A Cry from Norway’s Civil Wars ....

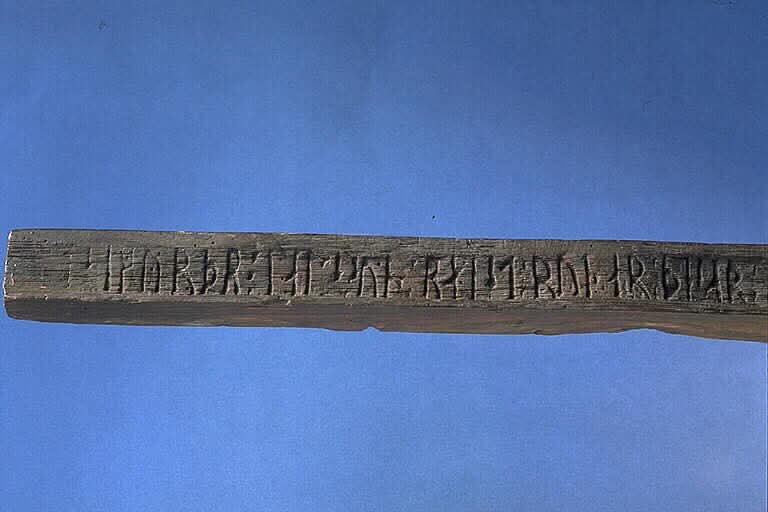

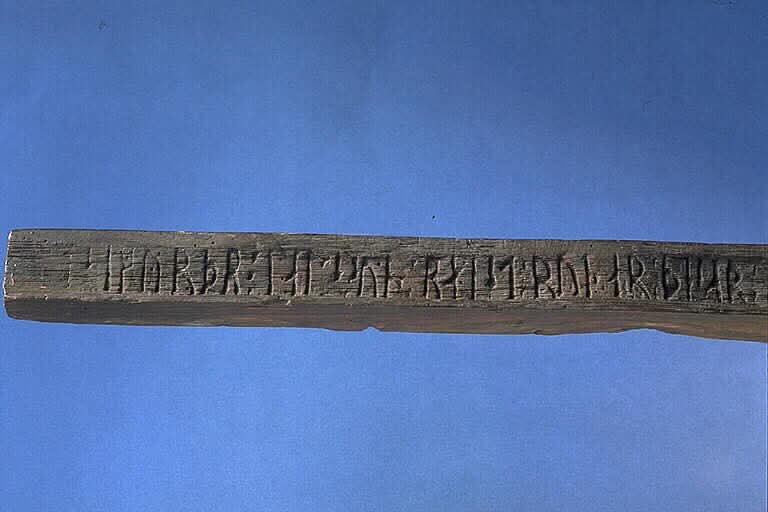

In the doorway of Vinje Stave Church in Hordaland, a rare runic inscription tells a dramatic story from one of the bloodiest chapters in Norwegian history:

"Sigurd Jarlsson carved these runes Saturday after St. Botulph’s Day when he fled here and refused to enter into a plea deal with Sverre, his father and his brothers' bane."

The inscription likely dates to the late 1100s or early 1200s, during Norway’s brutal civil war era—a time when rival factions battled over the throne for generations. The man Sigurd fled from was King Sverre Sigurdsson (reigned 1177–1202), a former priest who rose to power as leader of the Birkebeiner rebel faction.

Sverre claimed to be the illegitimate son of King Sigurd Munn and used this claim to challenge the reigning powers. Ruthless and charismatic, Sverre crushed his rivals, many of whom were members of the old aristocracy. Among them, apparently, was Sigurd’s family. Calling Sverre “his father and his brothers’ bane” was a direct accusation. Sigurd’s words suggest that Sverre was responsible for killing his relatives—possibly during one of the many violent clashes between the Birkebeiners and their enemies, such as the Bagler faction.

Sigurd’s refusal to “enter into a plea deal” shows that he was offered a chance to submit, perhaps even survive—but he chose exile and carved his defiance into the wood of a holy place.

The reference to “Saturday after St. Botulph’s Day” gives us a rare and precise date. The tone is not poetic—it’s political. This is not myth or legend, but a personal act of rebellion captured in a handful of runes.

What happened to Sigurd Jarlsson afterward is unknown. But his carved message survives—one of very few medieval runic inscriptions with such clear historical and emotional force. It stands as a defiant whisper from a man trapped in the storm of civil war, unwilling to bow to the man he blamed for destroying his family.

#archaeohistories

XXXXX engagements